In this review Jim Thompson discusses explain the process of capturing data to produce a narrowband Sulfur-Hydrogen- Oxygen (SHO) image using a OSC camera.

The final title I selected for this article, “SHO On-The-Cheap”, is perhaps not the most descriptive, but it is at least better than my original title: “What to do if you want to try narrowband imaging but have a one-shot colour (OSC) camera and don’t want to buy a new monochrome camera with a filter wheel and all that other nonsense.”

Thus, the objective of this article is to explain how one can capture data to produce a narrowband Sulfur-Hydrogen-Oxygen (SHO) image using a OSC camera. Let’s begin by first discussing what exactly a SHO image is.

Consider the well-known image of the Eagle Nebula shown in Figure 1, captured using the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The HST uses various narrowband filters to collect image data for each gas emission separately, including: Sulfur-II at 672nm, Hydrogen-α at 656nm, and Oxygen-III at 501nm.

This data is combined after-the-fact to form a synthetic image, one that does not actually exist in nature but that displays the collected data in an attractive and easier to interpret way. Narrowband imaging has many advantages for us amateur astronomers, but I’m not going to talk about that in this article. Instead, I am going to talk about what OSC camera owners can do if they want to try creating SHO images for themselves.

Multi-Narrowband Filters

The answer to the question of what OSC camera owners can do involves one of my favourite things: multi-narrowband (MNB) filters. Multi-narrowband filters are designed to have two or more narrow pass bands centered around desirable nebula emissions. They maximize nebula contrast by blocking as much light pollution (LP) as possible.

Because they pass light in both the blue/green range and red range, they produce full colour images with OSC cameras. These filters make electronically assisted astronomy (EAA) and imaging from light polluted backyards possible. Take for example the images shown in Figure 2. The upper image is what I could see of the Veil Nebula from my urban backyard after 10 minutes of exposure but no filter, and the lower image is what I could see after the same amount of time using a MNB filter with 3nm wide pass bands. Note that stars have been removed to make the differences in the visible nebulosity more apparent.

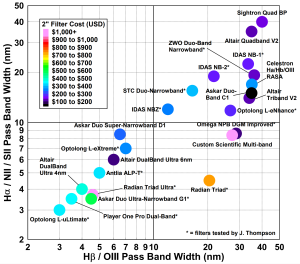

MNB filters have become quite popular in the last couple of years, and there are many brands and models available today. Figure 3 presents all of the MNB filters available commercially, plotted according to the width of their pass bands. The dot colour represents the cost of each filter in USD. I have a long history with these filters, having tested more than half of those shown here. In my experience the narrower the filter’s pass bands are, the more it is able to increase nebula contrast and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

These filters were developed primarily for use with OSC cameras, but they work with monochrome cameras as well. Using a MNB filter with my EAA setup there is pretty much no limit to what I can observe from my backyard.

Hyperspectral Imaging

Besides cutting through light pollution (LP) to get at wonderful views of nebulae, there is something else that we can do with MNB filters. We can use them to turn our OSC cameras into hyperspectral imaging systems. It so happens that emissions captured in the O-III band of the filter are picked up only on the OSC camera’s Green and Blue colour channels. Similarly, the H-α band is only picked up on the camera’s Red channel.

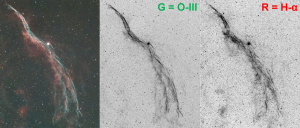

Thus, with one image captured using a OSC camera and MNB filter, we have collected 2/3 of the data we need to make an SHO image. This can be further demonstrated by deconstructing an image I captured from my backyard of the Western Veil Nebula as shown in Figure 4. If I extract just the green colour channel from the image we can see just the O-III emissions by themselves. Similarly, by extracting the red colour channel we can see just the H-α emissions. Thus, the use of a MNB filter helps to cleanly separate these two emissions from each other.

But what do we do about Sulfur? S-II emissions are also in the red part of the spectrum, so to capture them we need to take a 2nd image using a different filter. Lucky for us, filter manufacturers have already developed the custom MNB filters we need to take that 2nd image containing S-II.

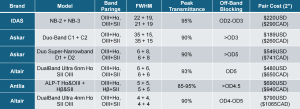

Figure 5 provides a table that summarizes the MNB filter pairs that are commercially available today, along with some filter properties such as band width and price. The IDAS NB-2 and NB-3 listed at the top are the first filters of this type to be sold, being available since late 2020. The Askar and Altair offerings are all very recent additions to the list, being released within the past six months. The sharp-eyed readers out there have probably already noticed that there is a large range in the price of these filter pairs, a property that is directly related to the quality and capability of each brand of filter pair.

MNB Pair Testing

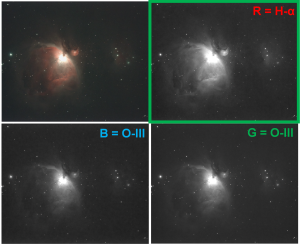

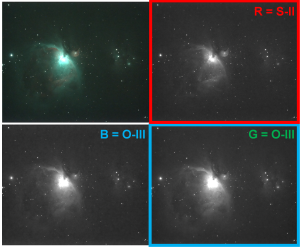

I have had an opportunity to try two brands of MNB pair, the first being the IDAS pair that I played around with about 3 years ago. Figure 6 shows how the NB-2 filter image looked, a stack of 15 x 20 second sub-exposures. The monochrome images in the figure show what we get when we split the image into its colour channels.

The second image, captured using the NB-3 filter, is shown in Figure 7 along with its corresponding monochrome channel images. To assemble my SHO image I used the three channel images circled with the coloured boxes in Figures 6 and 7 and ignored the rest.

My end result is shown in Figure 8. I found the S-II emission to be weak relative to O-III, which made picking the best sub-exposure time difficult. The weak S-II signal also meant that a lot of stretching of that channel was necessary for it to contribute at all to the final image, which resulted in a noisier image.

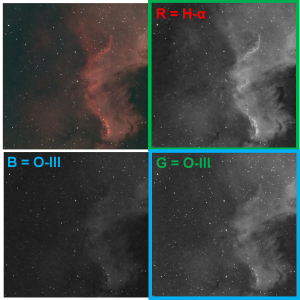

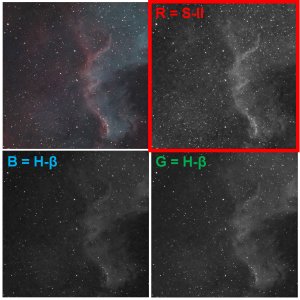

My second attempt was made more recently using the Antlia brand pair. Figure 9 is the image I captured using the normal ALP-T filter, a stack of 5 x 120 second sub-exposures, and Figure 10 is the image captured using the second filter in the ALP-T pair.

To assemble my SHO image I used the three channel images circled in the colour boxes and ignored the rest. My resulting SHO image is shown in Figure 11. The contrast and detail in this image are much better than that captured using the IDAS filter pair because this pair has much narrower pass bands. I found that Antlia’s idea of pairing S-II with H-β rather than O-III was a good choice as it was easier to manage my sub-exposure times. Unfortunately, this filter pair is 3x the cost of the IDAS pair, although the total price is still significantly cheaper than having to buy a 3-filter narrowband SHO set.

Final Comments

I encountered some limitations when using these filter pairs, the first related to camera resolution. Due to the Bayer matrix applied to the OSC camera’s sensor, only 1/4 of the sensor’s pixels are actually collecting Red data, and only ½ the pixels are collecting Green data. As a result, the effective resolution of my SHO image is reduced. If I were using a monochrome camera with three separate SHO narrowband filters, data for each emission would be collected using all the sensor’s pixels.

The next thing I found was that setting the sub-exposure time and total number of frames was a challenge. A nebula’s emission of O-III, H-α and S-II are not of equal strength, so I should be using a different sub-exposure time and number of subs for each emission to get the same SNR. Since I am capturing two emissions at the same time, it is often the case that one band is under exposed to prevent the other from being over exposed.

Another thing to note is regarding filter availability. There are numerous choices of narrowband SHO filter sets, but only the MNB filter pair choices listed earlier are available presently. Perhaps if these filters become popular there will be more offerings available, but until then these are all we have to choose from.

An important thing to note is that not every emission nebula has a pretty SHO image waiting to be revealed. S-II is not prevalent in every nebula, limiting what objects can be imaged in this way. There is some excitement buried in this observation however as it presents an opportunity for one to explore the list of well-known emission nebulae and discover for themselves if they have an S-II emission.

It may not be obvious from my output images but if you zoom in you will see my stars are really messed up. This is due mostly to having to severely stretch the image containing the S-II data in order to get a significant contribution to the end result. A lot more care is required to get nice looking stars in SHO images, essentially by post processing the stars separately from the nebulosity – a time investment I am not sure I am willing to pay.

My final comment on the idea of using a MNB filter pair with a OSC camera to produce SHO images is that the whole experience was kind of fun. It gave me a new way to look at and better appreciate some of my favourite deepsky objects. This was however at the expense of more time doing post processing, which is perhaps fine for an astrophotographer but not-so-much for someone focused on EAA.

If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me. top-jimmy@rogers.com. Cheers!

Jim Thompson acquired his passion for astronomy growing up under the dark skies of Eastern Ontario (Canada) cottage country. He has over 25 years of experience working as an Aerospace Engineer in the defense industry and enjoys applying that same skill set to his amateur astronomy hobby. Jim is a strong advocate for Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) which he uses frequently from his urban home in Ottawa, Canada. The severe light pollution in his backyard is the primary impetus for him becoming an expert on astronomical filters. You can follow Jim’s efforts at his Abby Road Observatory website (http://karmalimbo.com/aro/) where he documents his journey with amateur astronomy.

And to make it easier for you to get the most extensive news, articles and reviews that are only available in the magazine pages of Astronomy Technology Today, we are offering a 1-year magazine subscription for only $6! Or, for an even better deal, we are offering 2 years for only $9. Click here to get these deals which only will be available for a very limited time. You can also check out a free sample issue here.

And to make it easier for you to get the most extensive news, articles and reviews that are only available in the magazine pages of Astronomy Technology Today, we are offering a 1-year magazine subscription for only $6! Or, for an even better deal, we are offering 2 years for only $9. Click here to get these deals which only will be available for a very limited time. You can also check out a free sample issue here.