The AAVSO is hosting a Winter Imaging Challenge of NGC 457, The Owl/ET Cluster and inviting all amateur astronomers interested in helping make a contribution to science to participate through the photometry project.

About the Project

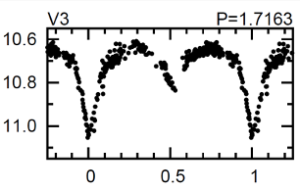

V765 Cas is an Eclipsing Binary – a pair of stars that orbit around each other. The orbits are aligned just right, so that periodically (once every 1.72 days), the fainter star blocks the light from the brighter star, making their combined light drop by about half a magnitude. The situation is very similar to Algol. The light curve from the discovery report is shown in Image 1, in which you can see that, like Algol, the system displays a primary and a secondary eclipse. The brightness drop at the bottom of the primary eclipse is about 0.4 magnitude, and the duration of the eclipse (start to finish) is about 8 hours.

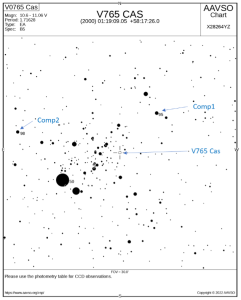

As the AAVSO notes, “V765 Cas also happens to be a neglected system – it appears that nobody has paid attention to it since its discovery in 2008, despite the many wonderful images (like the one shown in Image 2) that have been made of the cluster this star resides in. There are no observations in the AAVSO database, and none in the O-C gateway. A modern observation of the eclipse will confirm the orbital period and improve the precision of the period. An updated ephemeris will provide better predictions of the times of future eclipses. That, in turn, will simplify the scheduling of telescope time by researchers who are conducting targeted photometric and spectroscopic observations.”

Targeted observations of eclipses to collect multi-color light curves will facilitate modeling of the system to understand the temperature and relative sizes of the two stars. Longer term, additional eclipse timings (say, every year or so) can monitor for changes in the orbital period, enabling us to determine whether the period is constant or changing.

As AAVSO notes also notes, “It may be surprising to learn that for some eclipsing binary systems, the period does gradually change, and it can happen for a variety of reasons: a third star in the system is “pulling” on the eclipsing pair, there is a mass exchange between the two stars, there is a mass loss from the system (e.g. stellar wind), or there are magnetic interactions. All of these occurrences have been detected on binary stars by this type observation and analysis, and we would love to better understand this system as a result of your observations. In case you were wondering: yes, V765 does appear to be a member of the NGV 457 cluster, based on its parallax and proper motion!”

How to Participate in the AAVSO Winter Imaging Challenge

The AAVSO is encouraging participants to spend several hours the night prior to the predicted eclipse, the night it occurs, and the night after, focusing on the cluster with their imaging setup, making a long series of images. Any filter is okay, as well as unfiltered images.

The longer you observe each night, and the more nights you accumulate, the more likely the AAVSO is to capture an eclipse. In general, if you were to collect 8 hours of time-series images per night, over three consecutive nights, you are almost certain to get at least a portion of an eclipse light curve. For advance planning, you can see the eclipse predictions by going to the AAVSO’s Variable Star Index for V765 Cas and clicking “Ephemeris.” These are merely predictions due to the error that may have accumulated in the ephemeris data since the last reported eclipse timing.

Dates for Observation for the AAVSO Winter Imaging Challenge

The following are the predicted nights when V765 Cas will have an eclipse observable from North America. It would be ideal if you can take a short set of images on the night before a predicted eclipse, then a long series (three to four hours) of continuous images of NGC 457 on the night of a predicted eclipse, and another short set of images on the night after.

The upcoming USA evening dates (not UT) are: 2022 Dec. 31; 2023: Jan. 7, Jan. 12, Jan. 19, Jan. 24, Jan. 31.

Imaging Overview

Unfiltered images, or any combination of imaging R-G-B filters, or photometric B-V-R filters, or single-shot color (including DSLR) images will be fine for this project. You want to be able to reach about 12th–13th magnitude stars in the image, which should not be a problem for most imaging setups.

There are three suggested requirements for your images to support the photometry project:

– The image time should be in the FITS header and should be accurate to ± a few minutes (or better).

– The filter used should be clearly identified in either the FITS header or the file name. Single-shot color or DSLR images are acceptable, if DSLR images are taken in “Raw” mode, not JPEG.

– It is imperative that the star images not be saturated (aside from the two very bright stars marking the “eyes” of ET/the Owl). To avoid saturation, check your images and if necessary, adjust your exposure time.

The photometry processing cannot deal with over-exposed stars, so use an exposure duration that does not over-exposure the star images (no saturation or blooming). If the two brightest stars (ET’s eyes?) are overexposed that is OK, but the other stars should show nice “bell shaped” point spread functions, not flat-top PSF’s that are indicative of saturation in the star image.

Ensuring there is no saturation will be more challenging for those using CMOS imagers or DSLRs, both of which have smaller dynamic range than conventional 16-bit CCD cameras. A set of images that AAVSO made using a 6-inch F/10 telescope and an ASI-183MM CMOS camera (at gain=2) gave saturated stars with just a 60-second exposure; for this setup, a 20- or 30-second exposure was needed to prevent saturation.

You don’t need a pristine dark sky for good photometry. The photometry processing subtracts the background sky-glow around the target star and the comparison stars. Light pollution and even moonlight should not prevent from making images in support of this project. Similarly, if the focus is soft, or the images show a bit of trailing, that is not a problem: the photometry process sums the ADU count over all of the pixels in a star image, so it isn’t affected by modest amounts of defocus or trailing.

How to submit your data for the AAVSO Winter Imaging Challenge

When you have your first batch of images, you can send an e-mail to oca_bob@yahoo.com with the subject line “NGC 457 project,” and you

will get a response with a Dropbox location where you can upload your raw FITS files. Reduce your images with bias, dark, flat frames, but do not do any other processing (no summing, sharpening, etc.). The AAVSO wants each of your individual exposures (not a final summed image) in order to create a light curve from your time-series images.They will then run the photometry and send back a report. The AAVSO will run the photometry on everyone’s images to create a time-series light curve of the variations of V765 Cas, and send everyone participating a report with the results when the project is completed (forecasted for the end of January, 2023).

Try Photometry Processing Yourself

If you would like to try doing the photometry processing yourself, most modern image-processing programs have photometry routines (MaximDL, AstroArt, etc.). The AAVSO chart to shown in Image 3 provides the location of the target, V765 Cas, and the two calibrated “comparison stars” that they will be using.

If you have any questions about participating in the AAVSO Winter Imaging Challenge you can email the AAVSO at aavso@aavso.org or go to their website at www.aavso.org.

And to make it easier for you to get the most extensive news, articles and reviews that are only available in the magazine pages of Astronomy Technology Today, we are offering a 1-year magazine subscription for only $6! Or, for an even better deal, we are offering 2 years for only $9. Click here to get these deals which only will be available for a very limited time. You can also check out a free sample issue here.

And to make it easier for you to get the most extensive news, articles and reviews that are only available in the magazine pages of Astronomy Technology Today, we are offering a 1-year magazine subscription for only $6! Or, for an even better deal, we are offering 2 years for only $9. Click here to get these deals which only will be available for a very limited time. You can also check out a free sample issue here.

The sun is more active than it has been in years! If you’d like to learn more the technology behind solar observing, solar imaging and more, you can check out our free publication, “The Definitive Guide to Viewing and Imaging the Sun”. You don’t have to sign up or provide any information, simply click here and enjoy reading!