Astronomy Light Pollution Filters from Chroma Technology solve a big problem – Light pollution – every astronomer’s nightmare. Unless you’re lucky enough to live beneath a nice dark sky or have access to a remote observatory, you’ve had to learn to deal with unwanted light intruding on your pastime.

I don’t even bother trying visual observing from my home observatory anymore, except for occasional planetary and lunar sessions. Almost every evening that I’m up and running, I’m capturing data to make into images. Even when I go camping and set up shop in a field away from city lights, there is growing sky glow that makes my images less clean and harder to process. And it is only getting worse.

I’ve tried many different techniques for limiting uneven field illumination from my images. I built a light shield using PVC pipe and tarps to block nearby light from entering the telescope. That worked okay, but I had to set up everything each time I wanted to observe. I eventually built a small observatory so I could leave everything set up and have even more protection from light.

I no longer have stray light in direct line of sight of the telescope, but I still have a great deal of sky glow from various sources. So I have to work hard to remove gradients from my images while trying to retain the details of the night sky.

I’ve used several light pollution filters over the years. They helped reduce gradients but left an awful color cast to the image, creating extra work to deal with the color cast as well as the slight gradient that remained. They also forced me to use significantly longer exposures, because they also blocked some of the photons I want to capture.

I ventured into the realm of narrow-band filters so that I wouldn’t have to deal with light pollution at all, but that limits the potential objects I can image. I still use them sometimes, because they are fun and create interesting images, but I prefer traditional LRGB images.

Enter Chroma Technology and their latest filter, a truly-effective light pollution-reducing filter. The first thing I noticed about this light pollution filter is that is not nearly as opaque as any other filter I’ve been using. It’s also a very different color, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

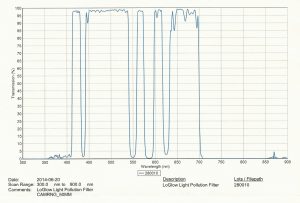

It turns out that the engineers at Chroma Technology have designed their filter to block only the common major Hg and Na lines: 365, 404.7, 407.9, 435.8, 546.1, 577.0, 579.1, 589 and 623 nm, and very little else. The Hg lines correspond to Mercury Vapor lights and the Na lines match up with Sodium Vapor lights. If you look at the transmission chart in Figure 3, you’ll see how tightly they have matched the wavelengths blocked to the Hg and Na lines. This means the filter will block the bad stuff but not much else. At least in theory.

So, just how well does this filter actually work? Well, as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. Take a look at Figures 4, 5 and 6. I was able to make these images from my light-polluted front yard (that’s where my observatory is) using the same two-minute exposures I use without filters. All these images were made using an Orion Deep Space Imager III through a Stellarvue SVR80 riding on top of my new Celestron CGEM. You certainly can’t accuse me of brand loyalty, can you? Actually, I can’t say enough about how much I like these products,

but that’s for another article. Suffice it to say, the only thing I changed about my setup for these images was the inclusion of the Chroma Tech LPR filter.

Using my normal processing workflow, I generated these images in very little time, and there isn’t a gradient to be found. I was able to eliminate the entire set of actions I usually use to remove or limit uneven field illumination. I did have a slight color cast to the entire image, but the Background Neutralization script in PixInsight killed that in seconds and left me with nothing but nice, balanced data to work with.

The image of M15 (Figure 4) was made using only 10 minutes each of Luminance, Red and Green data and took only about 30 minutes to process to the following result. This is by far my best globular cluster image to date and it took only 40 minutes of data capture to accomplish!

The image of the Andromeda Galaxy show in Figure 5 was a little more difficult because of the proportions of the galaxy relative to the image size. I still didn’t have any gradients to work out, but the color cast was a little harder to figure out. I still used that script in PixInsight,  but I had to give it a couple tries with different parameter settings to get it right. However, look how smooth the data is. The next time I take a shot at this object, I’ll use a combination of long and short exposures so I can bring out even more detail in the dust lanes while retaining the nice soft glow of the core.

but I had to give it a couple tries with different parameter settings to get it right. However, look how smooth the data is. The next time I take a shot at this object, I’ll use a combination of long and short exposures so I can bring out even more detail in the dust lanes while retaining the nice soft glow of the core.

The image of NGC 7331 shown in Figure 6 was made with only 40 minutes of Luminance and 20 minutes each of Red, Green and Blue. Go ahead, try to find uneven illumination in there. This object will also benefit from some longer exposures and more of them, but weather has been terrible lately and I didn’t have the patience to gather more data. I can stretch the data a bit more, but then noise due to underexposure creeps in. However, if you look closely you can see the little group of galaxies to the left and the little one just to the right of NGC 7331. If I enlarge the image, I find more of them scattered about.

So, what more can I say about this filter. For me, it’s a game changer. I no longer have to deal with gradient removal. I don’t have to double my exposures like I would with other LPR filters I’ve used. I have only a minor color cast to deal with (which is very simple).

And I generate images with nice, deep, dark backgrounds, and vibrant star colors and main object details. In other words, I’m eager to get out and make images from my light-polluted front yard, confident that I can once again make them with ease.

This filter is available in 1.25-inch and 2-inch size. If you need the filter in a difference size or configuration, contact them. I’m sure they’ll work with you.

Dave Snay is a retired software engineer living in Central Massachusetts. He graduated from Worcester Polytechnic Institute and has been an amateur astronomer and astrophotographer for a number of years. He also pursues fine art photography and enjoys traditional black and white images.

Dave Snay is a retired software engineer living in Central Massachusetts. He graduated from Worcester Polytechnic Institute and has been an amateur astronomer and astrophotographer for a number of years. He also pursues fine art photography and enjoys traditional black and white images.

And to make it easier for you to get the most extensive telescope and amateur astronomy related news, articles and reviews that are only available in the magazine pages of Astronomy Technology Today, we are offering a 1 year subscription for only $6! Or, for an even better deal, we are offering 2 years for only $9. Click here to get these deals which only will be available for a very limited time. You can also check out a free sample issue here.